In our last piece on residential electricity price increases (Aug. 2025) we took on the political narratives which were concerned primarily with the cost of generation, especially whether renewables were to blame. No points for guessing which side of the aisle took which side of the debate.

Our analysis disaggregated residential prices into their 3 main components: the cost of energy supply (i.e. generation), long distance transmission, and shorter distance distribution. We showed how only 1.5 cents of the 4.4 cent per kilowatt hour increase in average residential prices over the last ten years was from generation and transmission and the remaining 66% was from increases in distribution which have little or nothing to do with how or where the power was generated. We also showed the remarkable 95% correlation between the distribution component and the cost-of-living index for each state, which makes sense since local labor costs account for so much of distribution costs.

In this piece we focus specifically on the increase in the cost of generation and the growing difference in increases occurring in states where prices are set by the deregulated wholesale power markets (“deregulated”) versus states where virtually all the generation costs are part of the monopoly utility cost-plus model (“vertically integrated”).

Spoiler alert: in states with deregulated markets determining wholesale power prices, rising demand relative to supply has pushed prices higher. That’s right folks, you heard it here first, commodity prices in deregulated markets respond to supply and demand. Stop the presses.

Historical Prices for Wholesale Generation

Our analysis uses industrial prices as a proxy for the cost of generation – effectively a wholesale price – as these large users don’t pay very much for transmission and distribution. This is because supplying a large volume of energy to a single point is significantly less expensive per kilowatt-hour than distributing smaller amounts to thousands of individual homes spread across a wide area.

In the first half of 2025, the weighted average U.S. industrial rate was only 1.0 cents per kilowatt hour above the U.S. Department of Energy (“DOE”)’s estimate of the cost of generation for the same period, while the weighted average residential rate was 9.7 cents above the cost of generation.[1] The cost or price of generation reported by the DOE is calculated at trading nodes where most transactions are with intermediaries like the utilities and not final consumers so we thought for this analysis it was better to use actual user prices.

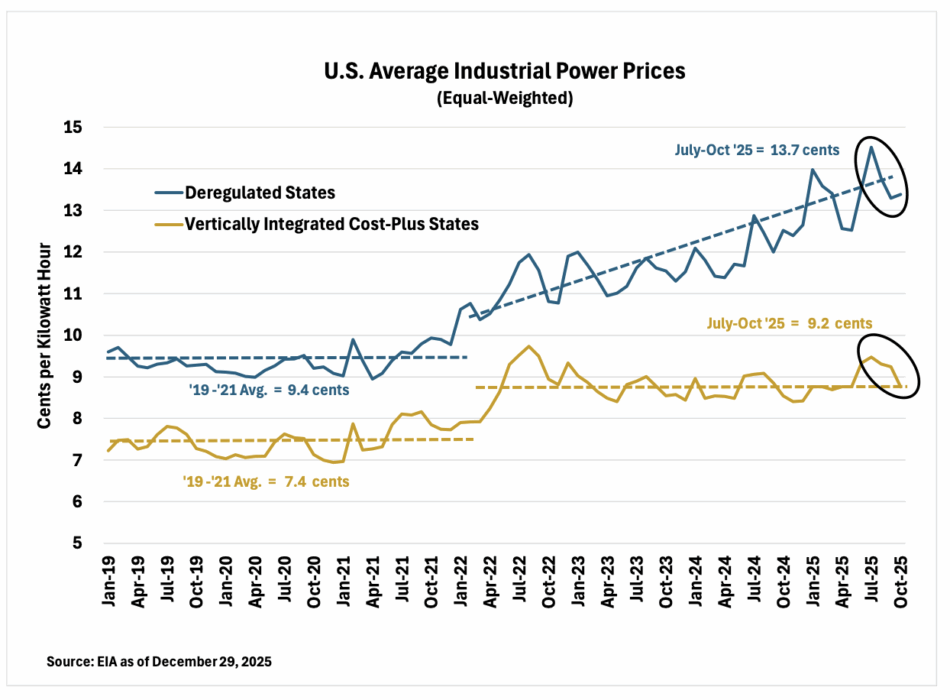

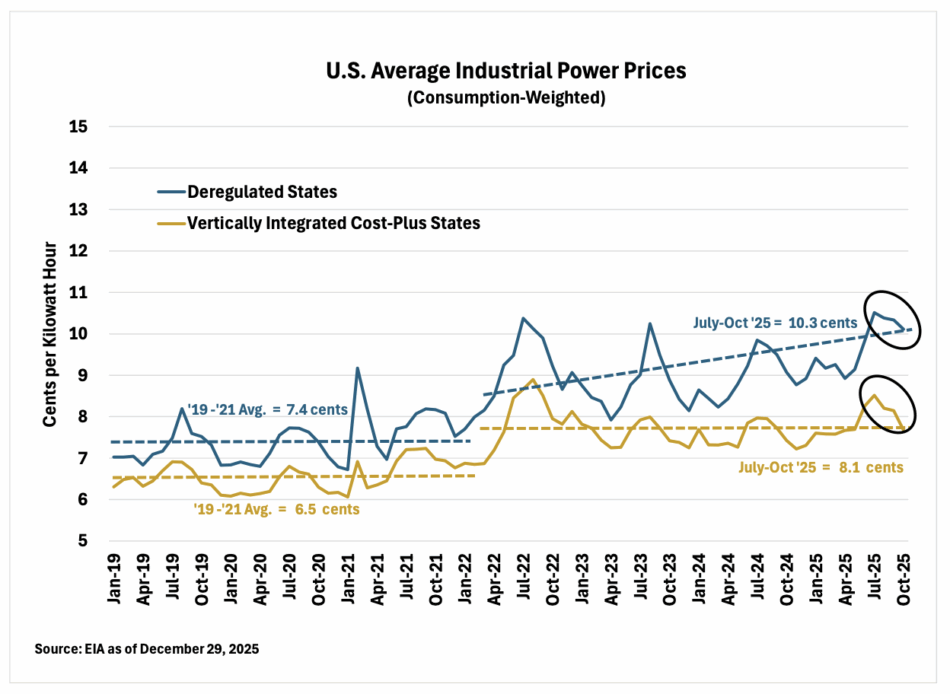

Exhibit 1 shows the results tracking industrial prices from before COVID through the last four months for which we have data from the DOE.

Exhibit 1 – U.S. Average Industrial Power Prices

In 2019[2] through 2021 the trends in cost for both these systems were moving along together. But over the last three to four years since demand has been rising (for the first time in 20 years), the pricing of these two systems has been diverging, as power prices in deregulated states have risen faster than in vertically integrated states.

What explains the difference, in our view, is that in deregulated commodity markets, prices are set by the marginal cost of incremental supply necessary to balance the market. Not so in vertically integrated states where power prices are part of the cost-plus revenue model for regulated utilities, where the average cost sets the price.

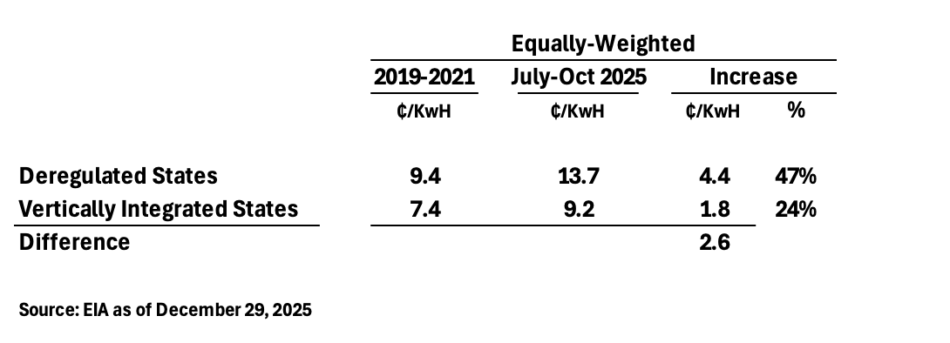

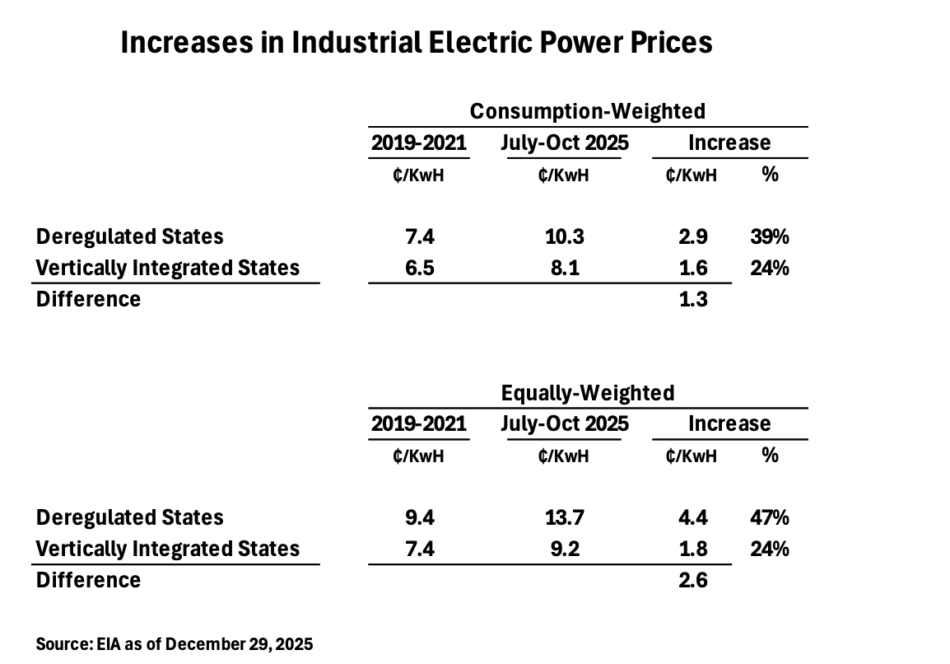

Here is the same data in tabular form:

Exhibit 2 – Increases in Industrial Power Prices by System

We compare the most recent four months of available data (July-Oct) from the DOE to capture both the peak seasonal demand in July (peak air conditioning) and the trough seasonal demand in October (trough air conditioning and heating). While the graphs show a clear change in trend, the table shows how large the difference is in price increases between deregulated versus vertically integrated states, nearly 2x the increase in percentage terms (47% vs 24%).

What is going on here?

Deregulated Commodity Markets

In all deregulated commodity markets, prices cycle around the cost of production for the high-cost suppliers (source: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776)[3]. Unless the market price covers the cost of the most expensive production needed to meet demand, supply will fall short of demand. That’s why the high-cost suppliers set the price for everyone. Of course, in the short term when there is too much supply, prices fall and vice versa when demand exceeds supply. But over the long term it is observable that those prices cycle around the cost of production for the higher cost suppliers. For electric power in the U.S., demand has been rising for the first time in 20 years, so in deregulated markets, successively higher cost power production equipment needs to be activated to balance the market (e.g. older, less efficient gas or coal power plants).

And when market participants look to add new generation capacity (i.e. power plants) they are experiencing 60-70% price increases versus 4-5 years ago[4]. And if current electricity prices have not risen enough to support those higher costs of new generation equipment, new supplies will not be added until prices – or price expectations – rise further. All to support the higher costs of just a small portion of the generation equipment needed to balance supply and demand. In competitive markets, prices are set by marginal costs, not average costs.

Deregulated wholesale markets for electricity generation were established in the 1990s and today represent about 42% of U.S. power consumption. Deregulation in the U.S. was driven by the massive cost overruns[5] for new nuclear power plants in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Back then every state operated under the vertically-integrated/cost-plus regulated monopoly pricing model and those cost overruns were passed along to all customers. But large power consumers, like industrial users, experienced prices that exceeded the cost of generating their own power, inducing them to “cut the cord”, leaving more and more of the system’s fixed cost to be borne by fewer and fewer customers who lacked scale to self-generate, like residential customers.

Something had to be done before residential prices skyrocketed as more and more large industrial customers left the grid, and deregulation of power generation at the federal level was the solution. The poles, wires and transformers in all states stayed in the state-regulated monopoly cost-plus model and now had to provide open access to merchant power generators. Did it work? Yes. Deregulation has lowered the real (inflation-adjusted) wholesale price of electricity since the mid-1980s by about 65%[6].

Vertically Integrated States

The other 58% of power generation supply comes from states that chose to keep power generation owned by their legacy monopoly utilities in the vertically-integrated/cost-plus model because they didn’t want the variability and uncertainty that comes with fully deregulated cyclical commodity markets. Sure, in free markets, supply will eventually respond to a higher price signal, but over what time frame? Building utility scale power generation plants can have lead times of over three years. What is the public supposed to do in the meantime, put up with more and more blackouts? Today 15 states and the District of Columbia are deregulated, and 35 states are vertically integrated.

In the vertically integrated cost-plus model, prices are set by adding up the approved operating costs plus the cost of capital investment and dividing all those costs by kilowatt hours used. The cost of capital investment includes interest on debt, and an allowed return on equity. Cost allocations result in lower prices for industrial users than residential users for reasons stated earlier.

This mechanism therefore has two fundamentally different dynamics than deregulated markets.

The first is that average costs of all generation built over the last few decades set the price, not the marginal cost of adding new capacity which may account for only 10% of the generation. Recent cost inflation affects a much smaller portion of the electricity bill in the cost-plus model than in the deregulated model.

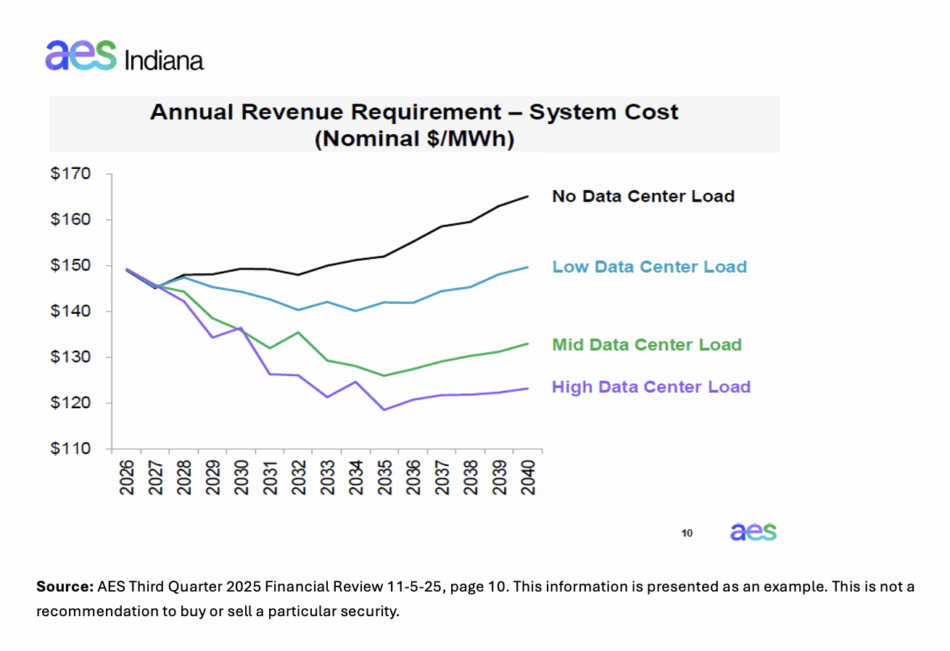

The second is that higher demand for vertically integrated utilities will actually put downward pressure on per kilowatt hour prices because about 80% of the costs paid by residential customers are fixed[7]. The recovery of the capital costs (via interest on debt and the allowed return on equity), fixed labor costs to maintain the system, property and income taxes, etc. do not vary with demand. If new demand comes into a vertically integrated state and new capacity is required, even at a higher cost than existing capacity, prices can actually decline as those costs are being divided by more kilowatt hours.

This is why AES Corp. came up with the graph below in their corporate presentation last November to explain why more data centers would lower residential prices in their vertically-integrated cost-plus utility in Indiana.

Exhibit 3 – Price Impact of More Demand in Vertically Integrated States- AES

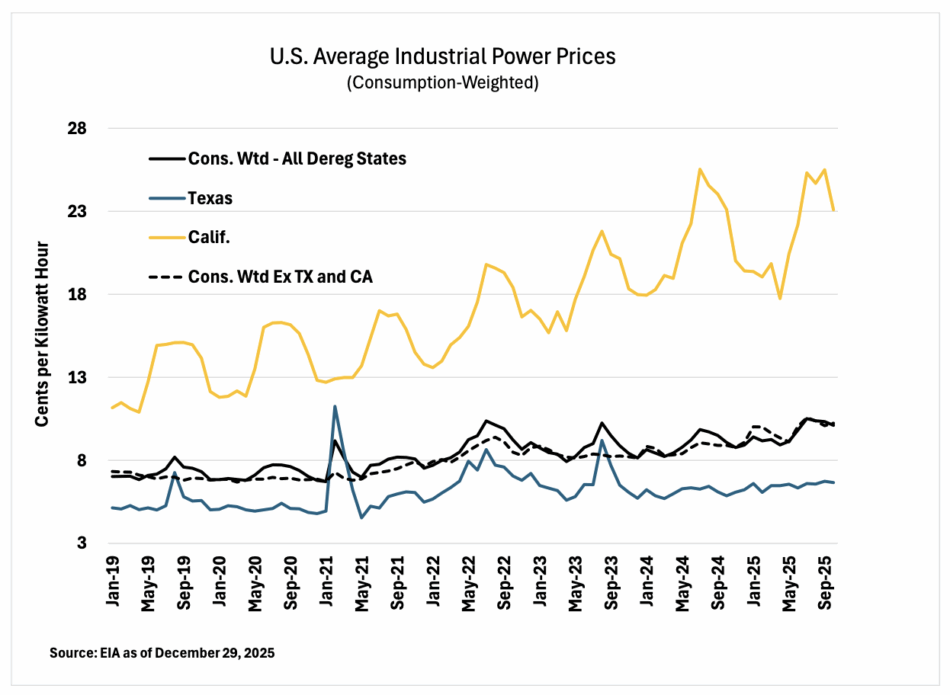

Deregulated States Industrial Power Prices-Consumption Weighted

The data presented in Exhibits 1 and 2 above weight the state-level price data equally. But there are significant differences between the states, especially among the 16 deregulated states (15 actually, plus the District of Columbia)[8]. There are also significant differences in usage. Texas, for example, accounts for 42% of the industrial demand for all deregulated states and has seen the lowest increases in industrial prices among all the deregulated states. July-Oct industrial prices for Texas are only 1.1 cents higher than the 2019-2021 comparison period (an increase of 19%) while California, which accounts for 11% of industrial demand for the deregulated states, industrial prices are up 10.7 cents (an increase of 76%). The graph below shows the industrial prices for Texas and the consumption weighted average for the 16 deregulated states in total and without the two outliers (CA and TX).[9]

Exhibit 4 – Deregulated States Industrial Power Prices – Consumption Weighted

Texas is so large relative to the other states that it has an outsized impact on flattening the trend shown in the first graph where all the statewide average prices are equally weighted. Nonetheless, the difference in price trends between deregulated states and vertically integrated states is clear.

Exhibit 5 – Deregulated vs Vertically Integrated Industrial Power Prices – Consumption Weighted

Here is the data in tabular format:

Exhibit 6 – Deregulated vs Vertically Integrated Industrial Power Prices – Consumption Weighted – Table

Texas has two attributes that are starkly different than the other deregulated states. The first is growth. Over the last six years (Jul-Oct 2025 vs Jul-Oct 2019) total power demand in Texas is up 15.6% versus the weighted average for the other deregulated states of negative 1.9%.[10]

The other is the lack of a capacity market. Many of the deregulated states, in conjunction with regional transmission authorities, establish a market mechanism to ensure a capacity cushion. Generators bid generation capacity into this auction generation capacity that they promise to keep ready to go so that seasonal peak demand can be met. The auctions provide payments for only one year, so it is not clear they provide a sufficient incentive to add capacity with a 30+ year life.

But in the face of increased demand and continued closures of aging coal and natural gas plants, the capacity auction for the region encompassing Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland (hence the abbreviation “PJM”), and all or parts of 10 other contiguous states and D.C. spiked in the last two years. The total payments to merchant generators across this region will average over $15 billion for each year from 2025-2027 up from an average of $2.2 billion in the previous two years, amounting to an increase of more than 1.5 cents per kilowatt hour.[11] These hefty payments, without a guarantee of added supply, is why Texas has rejected the idea of a capacity market.

To summarize, it should be no surprise to anyone that demand growth in excess of capacity growth will lead to higher prices in deregulated commodity markets, regardless of whether that commodity is copper, aluminum or electrons[12]. Nor does it matter whether the supply demand balance is tightening due to faster demand growth or shrinking capacity. And it’s not hard to understand that in a cost-plus system historic costs make up the bulk of the numerator, and that growing demand expands the denominator, so all else equal, tends to lower per-unit prices. The vertically integrated states have experienced 6.0% demand growth over the last six years (versus negative 1.7% for the deregulated states, ex-Texas). This, combined with their cost-plus, average-cost pricing system explains why their industrial prices are essentially flat over the last four years when inflation is up 19%.[13]

So Which System is Better?

We are not arguing that one system is better than another. Without deregulation it is highly unlikely the U.S. would have experienced the 65% reduction in real wholesale power prices over the last 40 years. But while a system that is 100% deregulated will tend to be cost-efficient it may not necessarily be reliable. A system that is 100% regulated monopolies operating under a cost-plus revenue model will tend to be reliable but not necessarily cost efficient as the cost over-runs in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrated. Nonetheless, today’s rapid demand growth combined with the closure of older fossil fuel plants is putting more upward pressure on prices in the deregulated model than the cost-plus model. If the situation were reversed and demand fell, and more and more capacity became idle, deregulated markets would likely experience lower prices as prior capital investment goes unremunerated. In a cost-plus model, those historic costs would be recovered regardless of whether that capacity is being fully utilized.

Vertically-integrated cost-plus systems tend to be more reliable because governors and regulators are incentivized to approve utility capital investments that enhance reliability lest they lose their jobs if the lights go out. Since cost-plus utilities can only grow their earnings for their investors by growing the asset base upon which they earn their allowed return on equity, shareholders encourage more capital spending as well, which helps provide a generation and delivery capacity cushion during demand spikes.

It is this last reason that we see the vertically integrated states – with a couple of notable exceptions in the deregulated states of Pennsylvania and Texas – as taking the lead in adding always-available (“dispatchable”) generation capacity – primarily natural gas – necessary to attract new industrial and data center customers. And as the AES graph above shows, more demand in a cost-plus system increases the denominator and can lower residential rates. Data center operators would much rather be associated with price reductions than price increases, often making the fully vertically integrated utilities the supplier of choice.

As we go to press, the White House is pushing for data center operators to enter into long term (probably cost-plus) contracts with merchant power producers to backstop construction of new generation. This comes on the heels of a number of deregulated states considering new legislation that would allow their poles-and-wires utilities to add generation on the cost-plus model. If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

One final note. There is increasing buzz about how the underlying cause of electric power price increases is these “damn monopoly utilities that have no competition”[14]. Our analysis shows otherwise – and lest people think that an investor-owned monopoly operating on a cost-plus system is socialism, know this: of the 35 states that operate under the vertically integrated cost-plus monopoly structure, fully 28 are red states while 13 of the 15 deregulated states are blue.[15]

So, the next time you read an article about what is driving increases in power prices and the author does not distinguish between the two pricing systems we have in the U.S. – deregulated versus vertically integrated – the conclusions are probably wrong. People who know how the system works usually don’t write articles (present company excluded) and the people who write the articles usually don’t know how the system works.

Don’t fight the system.

Understand it.

Addendum: Further Reading on Residential Prices in Deregulated vs. Vertically Integrated States

Since residential prices (versus industrial and commercial) are at the center of the current policy debate, we wanted to add this appendix regarding residential rate increases in deregulated states versus vertically-integrated cost-plus states. Remember, all states, whether deregulated or vertically integrated, operate the transmission and distribution assets in the cost-plus regulated monopoly pricing scheme and so all-else equal the wholesale pricing mechanism for power generation should not be a factor. But of course, all-else is rarely equal.

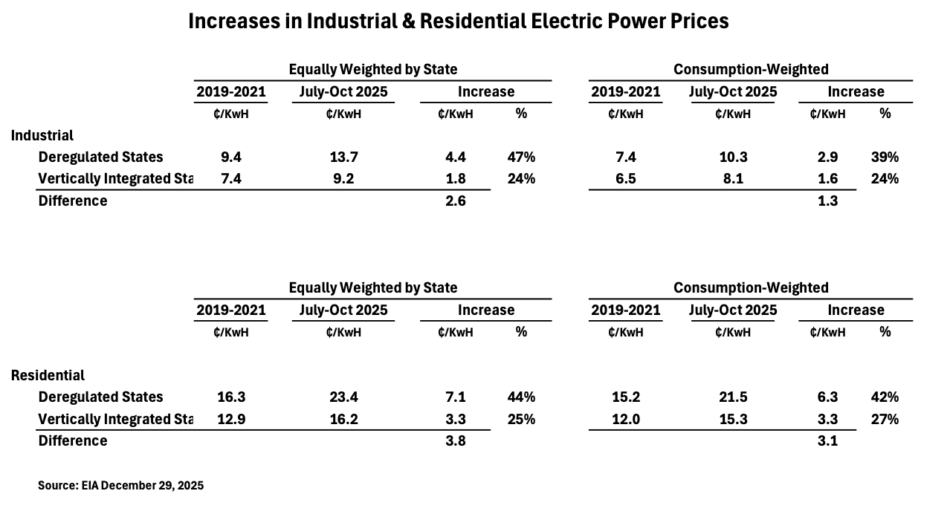

As shown in the table below in deregulated states, residential rates have increased more in cents per kilowatt hour than for vertically integrated states.

Exhibit 7 – Residential and Industrial Power Prices – Consumption Weighted – Table

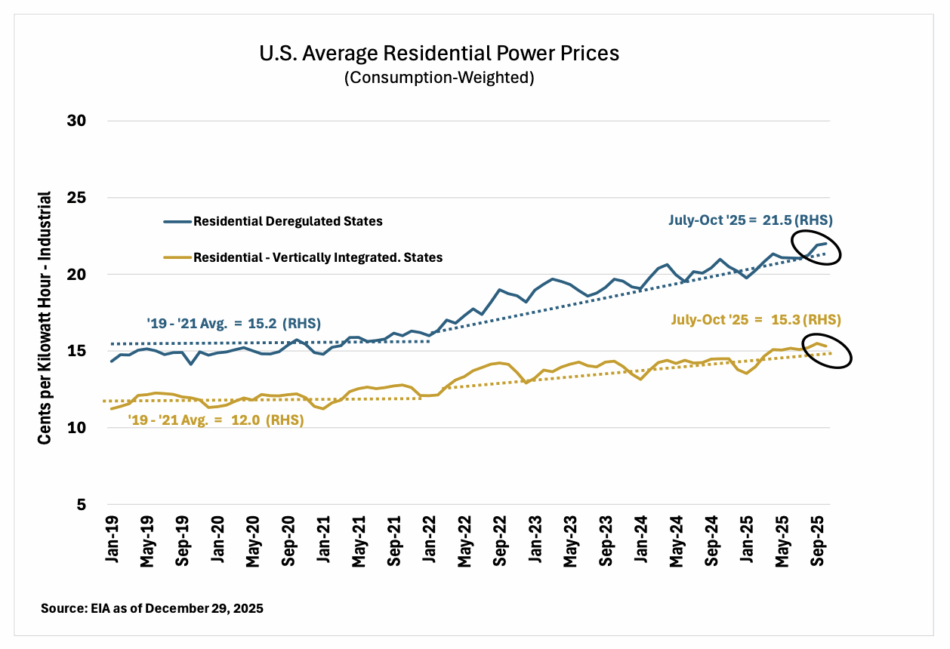

On a consumption weighted basis, residential rates in deregulated states are up 6.3 cents in July-October of 2025 versus the 2019-2021 average, while prices in vertically integrated states are up only 3.3 cents.

Why is that?

There are two dynamics at work. The first is the cost of electricity supply, which has risen more in deregulated states due to the market dynamics described above. In cents per kilowatt hour, that difference is 2.6 cents or 1.3 cents per kilowatt hour depending on whether we weight the changes equally for the states or weight the changes by consumption.

The second is inflation in distribution costs is acting on a higher number for the deregulated states than for the vertically integrated states. Consumption weighted residential rates in the 2019-2021 period were 15.0 cents for deregulated states versus 12.1 cents for vertically integrated states.

Why is that?

In our previous piece on residential prices, we showed the high correlation between the cost of distribution and the cost-of-living index of the states. Well, as it turns out the 16 deregulated states have a higher average cost of living than the vertically integrated states. On an equally weighted basis 111 versus 99. Weighted by power consumption it’s 107 versus 97.[16]

Said another way, in deregulated states residential rates are up 6.3 cents in the last quarter versus the 2019-2021 average, which is 3.4 cents higher than the increase for industrial customers, reflecting, in our opinion, the impact of inflation on the distribution part of the cost structure. In vertically integrated states residential rates are up only 3.3 cents, which is just 1.7 cents more than for industrial customers reflecting a lower starting point in states with lower cost of living indexes.

Here is what it looks like in graph form:

In summary, residential rates in deregulated states are being driven higher than in vertically integrated states for two reasons. The first is the price setting mechanism in competitive markets for power when the supply/demand balance tightens. The second is because the cost of delivery – a cost plus system in all states – is higher on average in deregulated states because, on average those states have a higher cost of living and labor and other inflation is acting on a higher starting point.

The information is based on data obtained from third party publicly available sources that EIP believes to be reliable, but EIP has not independently verified and cannot warrant the accuracy of such information. The analysis provided by EIP contains EIP’s opinions regarding the industry and regulatory environment surrounding the industry which may change at any time without notice. EIP has made a number of assumptions in its estimates shown in the piece above, any changes to such assumptions will alter the information presented. This Document is not intended to constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice or investment recommendations of any particular security or industry.

[1] EIA as of December 29, 2025

[2] We wanted our starting point to be pre-COVID

[3] See Chapter 5 “Of the Real and Nominal Price of Commodities” and Chapter 6 “Of the Natural and Market Price of Commodities”. And then there is this famous quote: “The real price of everything, what everything really costs to the man who wants to acquire it, is the toil and trouble of acquiring it.”

[4] Corporate reports and EIP estimates. EIP makes a number of assumptions in its estimates that it believes to be accurate. However, any change to those assumptions could affect the analysis above.

[5] Cost overruns of 3-5x were common, source: Univ of Pittsburgh. http://www.phyast.pitt.edu/~blc/book/chapter9.html#:~:text=Several%20large%20nuclear%20power%20plants,caused%20the%20remaining%20large%20increase?

[6] EIA as of December 29, 2025

[7] EIA as of December 29, 2025 and EIP estimates.

[8] No, I am not advocating for statehood for D.C.

[9] EIA as of December 29, 2025 and EIP Estimates

[10] EIA as of December 29, 2025 and EIP estimates. There is still price pressure in deregulated states due to closures of older generation plants and lack of new capacity. The results of the PJM capacity auction discussed below bear this out.

[11] PJM, EIA, Utility Dive: “PJM Capacity Prices Hit Record High as Grid Operator Falls Short of Reliability Target”, Dec 18. 2025, and EIP estimates. There are large differences between states and demand centers (“load pockets”) within states due to a complex cost allocation methodology. This average results from dividing the incremental $12.8 billion by the total annual kilowatt hours consumed in PJM.

[12] Ok electricity geeks, I know that in an alternating current system, it is not the electrons that are flowing across a wire but an electromagnetic field of energy travelling at the speed of light. To quote Science Simplified for All: “It’s not electrons moving through the grid like water in a pipe, but rather an electromagnetic (EM) field propagating around the wire, carrying energy near the speed of light, while the actual free electrons in the wire just “jiggle” back and forth very slowly (drift), bumping into atoms and transferring the field’s energy to the load (like a lightbulb). Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TVtn4gmdyog

[13]U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 20, 2026

[14] Tom Steyer, former hedge-fund manager and candidate for California governor has been beating this drum of late. Mr. Steyer fancies himself as an expert on energy and climate. He’s not.

[15] Also, the vast majority of cost-plus monopoly utilities are investor owned while some are owned by the federal, state or municipal authorities. Socialism is a system whereby the government owns the assets, not private investors.

[16] Missouri Economic Research and Information Center 3Q 2025