A Shifting Narrative.

As noted in our June 2, 2021 Insights post, two proposals before the California Public Utilities Commission recommended adding between 500 and 1,500 megawatts (MW) of incremental natural gas-fired generation as part of a broader 11,500MW expansion of in-state power generation capacity. This quickly unraveled as the state’s three investor-owned electric utilities balked at contracting for something that might leave them holding a bag of unrecoverable stranded costs.

On June 24, 2021, yet another proposed decision dropped the suggestion for new natural gas generation, instead recommending extending the current 2021 closure date for Redondo Beach, an existing gas plant, to 2023. This decision also points out that keeping natural gas plants available (that probably would only run for short periods of time) is preferable to having back-up generators–often dirtier diesel-powered–kick on when demand exceeds supply, and blackouts are inevitable. So, the narrative shifts from closing every natural gas fired generation plant, to keeping them and trying to minimize their use. This is an important shift, in our view, because it indicates the politics of having a “pure” non-fossil fuel fleet of generators is being matched by the politics of having a reliable power grid.

Running for Cover on Grid Reliability.

According to Bloomberg, the California Grid Operator (CAISO) is considering awarding two “reliability must run” or RMR contracts totaling less than 300 MW with two gas-fired co-generation facilities. An RMR contract is effectively an insurance policy that subsidizes an otherwise unprofitable plant that’s occasionally needed to assure reliability. In our experience, RMR contracts are done to support strategically located generating facilities essential to maintaining reliability in remote or transmission-constrained regions, often on the outer edges of the utility grid. Michigan’s isolated Upper Peninsula is a good example, where RMR contracts were used to keep older power plants from retiring, which would likely have caused reliability problems. California has also entered into RMR contracts for specific locations, but this is the first instance we’ve seen aimed at providing system-wide reliability instead of targeting a particular at-risk location.

While 300 MW represents only 0.4% of California’s 80,000 MW capacity, it is another move that shows the politics about gas-fired generation are shifting. In our view, California’s aggressive push to shut down older gas (and nuclear) generators has elevated what’s called single-point failure risk, a concern that blackouts could happen even if a relatively small generating resource is unable to deliver when needed. This situation will only get worse when the 2.5-gigawatt Diablo Canyon nuclear plant, about10% of the state’s electricity supply, shuts down in 2024. While RMRs are not that uncommon, one Federal Energy Regulatory Commissioner sees RMR as a symptom of broader California’s power market failure.

How About Natural Gas Reliability?

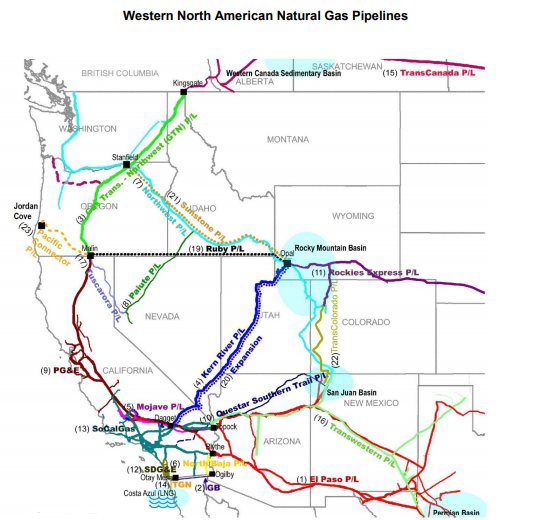

CAISO may also be fretting over deliverability of natural gas into the state, particularly as it affects some critical gas-fired generating plants. As a coastal state, with limited natural gas production inside its borders, California relies on several major interstate pipelines to import gas from Canada, the Rocky Mountains, and the Southwest as illustrated in the map below. Nearly 40% of California’s natural gas comes from the southwestern U.S., mostly the Permian Basin in New Mexico and Texas. The southern-most part of the state is wholly dependent on a single source of gas deliveries from Kinder Morgan’s El Paso pipeline at the California / Arizona border.

Texas, of course, experienced record-setting cold weather in February, which, triggered not just rotating electricity blackouts, but significant curtailments of its gas exports. Curtailments of the westbound volumes on the El Paso and Transwestern systems (the red and light green colored lines on the map) resulted in SoCal border gas prices surging 850% from around $3.00/MMBtu to over $100/MMBtu on February 16, 2021, and a spike in northbound flows of gas from Mexico during the same time period.

Source: 2016 California Gas Report, Prepared by the California Gas and Electric Utilities.

California has historically been able to handle this sort of brief supply disruption because of a large natural gas storage capability, principally in old oil producing reservoirs such as the one at Aliso Canyon north of Los Angeles, the second largest gas storage facility in the U.S. But since the 2014 gas leak that forced an extended shutdown of its operations, Aliso Canyon came back in service with only half its operating capacity. A pipeline that would have allowed the southern system to draw on gas storage further North and mitigated the single-point delivery risk described above was proposed by the utility SoCal Gas but was denied by the California Public Utility Commission.

Conversations we’ve had with a number of industry participants suggest that California drew heavily on its stored gas at Aliso Canyon and other facilities when imports were curtailed during the extreme February weather. While those curtailments were driven by winter conditions that won’t repeat in the summer, large heat events (like June 2021) spike demand for gas-fired generation across the region (Phoenix, Las Vegas), meaning there might be less gas at the end of the pipe to deliver to California. The very southern part of the state hosts a lot of solar and some strategically located gas-fired power plants…but gets all its gas from one pipe and has no storage. What me worry?

What’s the Takeaway?

In our view, California’s aggressive push to close little-used vintage natural gas-fired power plants was a key factor that drove the rotating blackouts during the August 2020 heat wave. However, the signing of systemwide contracts with older, inefficient facilities that don’t source gas from Texas–the recent RMR’s are with generators supplied by the Kern River pipeline, the blue line on the map that delivers gas from Wyoming—and the delay of planned closures of larger gas-fired generation facilities suggests perhaps California is coming to terms with the reliability of its energy system. These recent moves indicate that using more natural gas fired generation in multiple locations is not the political third rail that it used to be.

The Information provided in this article is believed to be accurate as of the date above. EIP reserves the right to update, modify or change information without notice. Any statements of opinion are EIP’s opinion and should not be relied upon as a prediction of any future event. The information is based on data obtained from third party publicly available sources that EIP believes to be reliable but EIP has not independently verified and cannot warrant the accuracy of such information. Investors are encouraged to seek their own legal, tax, or other advice before investing. EIP is not responsible for any information provided in third party links.