What is CCUS?

Carbon capture, use, and storage (CCUS) is the catch-all term for a variety of methods and technologies that remove CO2 from the flue gas of power plants & other industrial processes or directly from the atmosphere (called direct air capture, or DAC). This is followed by either recycling the CO2 for use in other applications – whether that be industrial processes or for enhanced oil/gas recovery (called EOR), or by permanently sequestering it underground in geologic formations and oceans.[1] In between the capture and use/storage of CO2 lies transportation infrastructure, typically a network, or hub, of pipelines. Regardless of the method, the end-goal is the same: net-negative or taking carbon out of the atmosphere as opposed to simply reducing carbon emissions.

CCUS technology has been around for nearly 100 years, though newer methods for both capture and use are still developing and remain expensive as the technology has yet to be scaled to reap the benefits of Wright’s Law (cost reductions through cumulative production) that dramatically lowered the cost of solar and wind energy. CO2 capture typically accounts for almost 75% of the cost of CCUS and can range from $25/t to more than $120/t, depending on the application and the concentration of CO2. DAC is even higher ranging from ~$150 – $350/t.[2]

In 2019, global CO2 emissions from fossil energy were 33 Gt/yr.[3] To meet climate targets, most policy makers around the world believe emissions need to fall to zero in the next 30 years. In our opinion, doing so without CCUS is nearly impossible without radical changes to human behavior, industrial processes, and how we heat, cool, power and transport within the global economy at large. Globally, the opportunity set for CCUS is massive. The IEA estimates that CCUS deployment needed to meet the Paris Accord goals would require investment of ~$9.7 trillion.[4]

The Biden Administration has a goal for the U.S. power sector to reach net-zero emissions by 2035.[5] To achieve this with affordable electricity prices and safe and reliable service, the Biden plan has always envisioned CCUS paired with existing power generation sources. From the Biden Plan: “Biden will double down on research investments and tax incentives for technology that captures carbon and then permanently sequesters or utilizes that captured carbon, which includes lowering the cost of carbon capture retrofits for existing power plants.”[6]

It is our view that CCUS projects that leverage existing infrastructure can speed the path to net-zero emissions, keep energy reliable and affordable, and mitigate the potentially significant “stranded asset” risk that strains traditional energy company valuations. Conversely, CCUS offers pipeline infrastructure companies a new revenue opportunity reflected in recent project announcements that we believe suggest multi-decade growth potential.

Joe Manchin’s Intervention

There has been a dizzying array of proposed energy, climate, and infrastructure legislation over the past several months from both the U.S. Senate and the Biden Administration, with a twin narrative of reducing GHG emissions across the US economy while creating new jobs. Enter Senator Joe Manchin, the Democrat from West Virginia, who has emerged as the key swing vote of the Biden era and is arguably one of the most influential participants in what is shaping up to be the largest U.S. infrastructure bill in over a decade. Manchin has been spinning a common bipartisan thread amongst much of this legislation: CCUS – and specifically the need for incentivizing more of it. In our view, no infrastructure deal gets done – and/or budget reconciliation for that matter – without incentives for CCUS. And that seems to be happening.

What’s New on the Policy Front

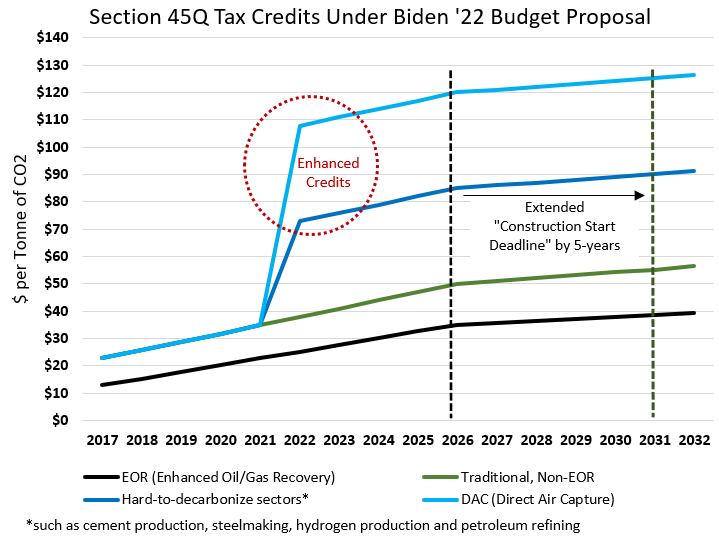

Two weeks ago, the Biden Administration outlined in the Treasury’s Green Book a proposed budget that included enhanced levels of tax credits for “hard-to-decarbonize” sectors like cement, steel and petroleum refining and for Direct Air Capture (DAC) technologies. Other proposed enhancements included extending the construction start-date by five more years to 2031 and the inclusion of a “direct pay” option that would reduce a project’s cost of financing by making the credit refundable and eliminating the need for tax equity.

The bump to this tax credit (often referred to as “45Q,” for its defining section of the Internal Revenue Code) could be $35/ton, raising the total tax credit from $50 to $85 per ton of CO2 captured and sequestered in the ground or beneficially re-used in a product like cement.[7] For CO2 sequestered from DAC technologies, which are still nascent and expensive, a $70 enhancement would bring the total tax credit to $120/t. The graph below shows a simplified history of this tax credit and the current proposed changes.

US Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals (“Green Book”) https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2022.pdf, EIP estimates.

Biden’s Plan also endorses Manchin’s bipartisan Storing CO2 And Lowering Emissions Act, or the SCALE Act. This Act aims to enable widespread deployment of CCUS through the formation of carbon transportation infrastructure and hubs which are seen as critical to addressing the chicken-and-egg conundrum around tying in carbon capture facilities to lower-cost transport and storage solutions that are enabled through larger-scale Hub-based infrastructure systems.

The “Energy Infrastructure Act” proposed legislation announced on June 21st, 2021, as part of the latest efforts for a bipartisan infrastructure bill, includes $12.1bn[8] in appropriations towards CCUS that draw from the SCALE Act.[9]

EIP’s Take

In our view, CCUS has always been essential to bipartisan support for any energy legislation because it garners needed votes from those representing fossil fuel and farmer interests. Since the advent of shale, states with large fossil fuel interests have expanded from Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma to include North Dakota, Montana, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Ohio and West Virginia.

Legislation that provides tax incentives coupled with policy certainty resulting in stable cash flows to investors usually succeeds in bring new capital to work. But this isn’t so much a forecast as a news report as the U.S. already accounted for 2/3rds of the world’s CCUS projects announced in 2020.[10] This is largely due to the enhanced 45Q tax credit that was updated under the 2018 Tax Cuts & Jobs Act, as well as tax credits available under California’s low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS).

The clean energy debate is also maturing beyond just carbon emissions to include methane which is 83x more potent in its near-term climate effect than CO2. Since agricultural waste and landfills are among the largest sources of methane emissions, the geographic interest in creating new revenues from methane abatement is quite broad. Geography, not population, is the arithmetic of the Senate.

Why it Matters to Investors?

Based on equity valuations, investor sentiment indicates exuberance for clean energy and pessimism for conventional energy. But, in our opinion, the arithmetic of decarbonizing the world economy by 2050 must include economic incentives to drive carbon and methane emission abatement. By our calculations, the agriculture and conventional energy industries combined can drive gigaton-scale reductions of GHG emissions if they can realize a new source of revenue for doing it. Our view is that finding a way to make that happen is exactly what’s being discussed in Washington right now.

Biden wants to decarbonize the power grid 15 years earlier – by 2035. In our view, the only way that happens without California-style blackouts is by CCUS enabling continued use of gas-fired generation as the cheapest and most reliable means of balancing the inherent intermittency of renewables. The costs we have seen for this indicate it will be a large part of achieving the 2035 goal.[11] How can the Administration offer an $85 CO2 credit to refiners who produce gasoline and not provide that same $85 to a power generator that will be needed to electrify the transportation system?

Since the 1970s the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act have reduced untold levels of pollution, not by shutting down industry but by requiring those industries to abate or dispose of their waste in places other than the nearby river or into the air. Over time newer, cleaner and more efficient factories replaced older ones. Why will reducing methane and carbon emissions be any different?

Why it Matters to The Public?

Climate change and energy transition are often framed around reaching net-zero emissions by a certain date (2050) to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The risk, according to scientists, is that a series of negative feedback loops could ensue if temperatures rise further. More heat could reduce ice caps that reflect heat back into space. More heat could release CO2 from the permafrost. More heat could raise atmospheric water vapor which is the most prevalent greenhouse gas.

This risk is driving a growing consensus across governments, researchers, and businesses that CCUS is a net-negative strategy critical to achieving deep decarbonization of power & industrial facilities and to moving the world closer to a net-zero emissions scenario. The IEA calls CCUS one of the four key pillars of the global energy transition, along with bioenergy, hydrogen, and renewables-based electrification.[12] According to the IEA, the global coal fleet accounted for almost one-third of global CO2 emissions in 2019, and 60% of the fleet could still be operating in 2050. Most of this fleet is in China where the average plant age is less than 13 years, and in other emerging Asian economies where the average plant age is less than 20 years. As former U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz put it, “…you can’t do net-negative if you don’t have net negative carbon technologies.”[13]

Therefore, in our opinion, CCUS is in many cases the only viable alternative to retiring existing power and industrial plants before the end of their useful lives and at great expense. Retrofitting CO2 capture equipment would enable the continued operation of existing plants, as well as associated infrastructure and supply chains, but with significantly reduced emissions within the accepted timeframe.

CCUS is a Big Opportunity for Pipeline Companies

In our view, pipeline infrastructure companies are particularly well positioned to create entirely new business platforms that will benefit from the emerging CCUS industry given their valuable rights-of-way, potential for further industry rationalization of overbuilt pipelines that can be repurposed, and multi-billion-dollar investment opportunities to create the necessary CO2 transportation hubs that connect capture facilities with end users and/or sequestration sites.

The most recent example of this potential occurred last week when TC Energy and Pembina Pipelines announced plans to jointly develop The Alberta Carbon Grid Project,[14] a hub-based carbon transportation and sequestration system. This project would re-purpose existing pipelines and add new ones to create a full-scale network capable of transporting more than 20 million tons per year of CO2, or 10% of Alberta’s industrial emissions.

In the U.S. today, ~5,200 miles of pipelines transport ~80 million tons per year of CO2, mostly for enhanced oil recovery where CO2 is pumped into a mature oil reservoir to drive out more oil. Princeton University estimates[15] that as much as 17x the current amount of CO2 could be transported by pipe, requiring 13x the current level of dedicated CO2 pipes compared to what’s in place today.

The U.S. also enjoys a logistical CCUS advantage: around 80% of CO2 emissions from power stations and industry are sourced within a radius of 50 km from potential storage sites (vs. China/Europe at just 45%/50%) and the total potential storage is estimated at 800 Gt, or 160 years of current US energy sector emissions according to the IEA.[16]

Is CCUS a New Investment Opportunity?

There is no shortage of estimates on how much CO2 must be captured and stored to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 Degrees Celsius[17] reviewed 90 scenarios and almost all required CCUS to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

90% of the IPCC’s scenarios required that global CO2 storage reach 3.6 Gt per year or more by 2050. The IEA’s 2050 Sustainable Development Scenario requires 5.6 Gt.[18] For perspective, in 2019 the U.S. emitted ~5.0 Gt of CO2, the world’s 2nd highest. The amount of anthropogenic CO2 captured globally in 2019 was just 0.04 Gt, less than 1% of what these models predict is needed.

Assuming an average facility capturing ~2 million tons per year, more than 2,000 capture facilities would be needed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The current global project backlog comprises only ~30 projects, but it is growing rapidly. Every week seems to bring the announcement of a new project. Stay tuned…

The Information provided in this article is believed to be accurate as of the date above. EIP reserves the right to update, modify or change information without notice. Any statements of opinion are EIP’s opinion and should not be relied upon as a prediction of any future event. The information is based on data obtained from third party publicly available sources that EIP believes to be reliable but EIP has not independently verified and cannot warrant the accuracy of such information. Investors are encouraged to seek their own legal, tax, or other advice before investing. EIP is not responsible for any information provided in third party links.

[1] American Institute of Chemical Engineer. https://www.aiche.org/ccusnetwork/what-ccus

[2] IEA (2020a), CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions, IEA, Figure 2.18, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions

[3] IEA (2020b), CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions

[4] IEA (2019), The Role of CO2 Storage, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-co2-storage

[5] Biden Administration, The American Jobs Plan. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/31/fact-sheet-the-american-jobs-plan/

[6] IBID.

[7] Source: US Treasury, General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals (“Green Book”) EIP Estimates.

[8] US Senate, Discussion Draft, https://www.energy.senate.gov/services/files/B09CFA1F-623B-433E-9D0B-39C752062D94

[9] Congress.gov. “Text – S.799 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): SCALE Act.” March 17, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/799/text

[10] Global CCS Institute, 2020. The Global Status of CCS: 2020. Australia. https://www.globalccsinstitute.com/resources/global-status-report/

[11] IEA (2020), CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions, IEA, (page 103 Box 3.3), Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions

[12] IEA (2020), Energy Technology Perspectives 2020, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-technology-perspectives-2020

[13] https://news.mit.edu/2021/3-questions-ernest-moniz-future-climate-energy-under-biden-harris-0128

[14] Pembina Pipeline Corp. https://www.pembina.com/operations/projects/alberta-carbon-grid-proposed/

[15] Princeton University, Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts, interim report, Princeton, NJ, December 15, 2020.

https://netzeroamerica.princeton.edu/img/Princeton_NZA_Interim_Report_15_Dec_2020_FINAL.pdf

[16] IEA (2020b), CCUS in Clean Energy Transitions, IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/ccus-in-clean-energy-transitions

[17] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (SR15), 8 October 2018.

[18] International Energy Agency. (2019). World Energy Outlook 2019. Flagship Report. https://www.iea.org/reports/worldenergy-outlook-2019