Energy MLP Income Fund, LP

1Q 2017 Letter to Investors

Performance

The Energy MLP Income Fund, LP (“EMIF”) was up 4.38% (net of fees) this quarter.1 This compares to the Alerian MLP Total Return Index (“AMZX”) which was up 3.95% and the Wells Fargo Midstream MLP Total Return Index (“WCHWMIDT”) which was up 3.93% over the same period.2

While the SEC requires us to use a benchmark when reporting our performance, bear in mind that nearly 40% of our portfolio is not in the broader Alerian MLP Index. That percentage is significantly lower than 12-18 months ago when we began to add significantly to our undervalued MLP positions. The balance of the portfolio is in companies not formed as partnerships involved primarily in transmission, distribution and storage of hydrocarbons, and the transmission and distribution of electric power.

While movements in the equity markets in general, rotations between sectors, interest rate expectations and commodity prices all have the ability to move our portfolio day to day, the yield of the portfolio, combined with capital appreciation – ultimately driven by earnings and dividend growth – drive our long-term returns.

Corporate Finance in the Energy Infrastructure Segment

In last quarter’s letter, we addressed questions regarding the change in Administration in Washington. That left us too little space to discuss another area in the current events arena related to corporate simplifications involving pipeline companies and their associated MLPs. There have been a number of such simplifications recently, and we have been getting a lot of questions about why they are occurring and what is driving them.

Simply put, these transactions are a way to reduce the cost of equity financing. What is not so simple to understand is the delicate balance that MLPs must strike to achieve and maintain a more attractive cost of financing than a typical “C” corporation. Unlike normal corporations, the MLP structure can actually lead to a higher cost of equity financing if the management team strings together multiple years of stable earnings and consistent dividend growth. While typically this sort of track record would lead to a higher valuation (and therefore a lower cost of equity financing), incentive payments paid by the MLP to its corporate parent that holds the general partner interest have the opposite effect. These payments, known as Incentive Distribution Rights (IDRs), have a long history so, in order to understand them, we need to look at MLPs as a source of equity financing in context.

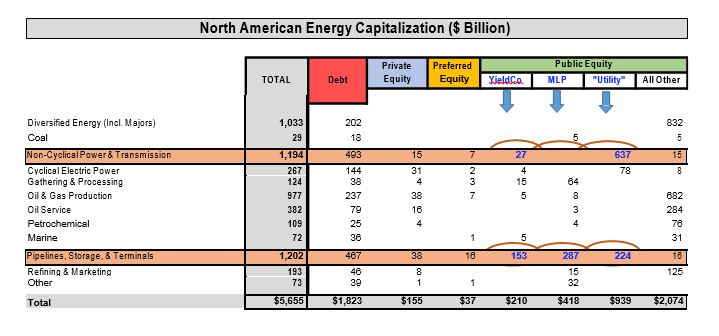

As background, let’s start with the entire North American Energy Industry split into its cyclical and non-cyclical components and divided between debt and equity (see Exhibit 1).

1 Past performance is not indicative of future results. Results include the reinvestment of dividends, interest and other earnings and are net of fees.

2 Indices do not incur fees and expenses.

Exhibit 1: Segment and Finance Summary of North American Energy Industry

Source: Factset. EIP calculations based upon Factset data as of 3/31/17.

The cyclical business segments include oil and gas production, trucking, shipping and processing, refining and marketing and merchant power generation. The non-cyclical segments are comprised of interstate pipelines, some storage assets, electric power transmission and distribution, gas distribution, regulated power generation and long-term contracted renewable power. The 1,342 companies behind this table include household names such as ExxonMobil, Haliburton, Williams Companies, Kinder Morgan, Southern Company, NextEra (formerly Florida Power & Light) and Enterprise Products Partners, the largest MLP and NextEra Partners, one of the largest YieldCos.3 Our portfolio is concentrated in equities of non-cyclical North American energy companies.

Let’s drill down a little further and split out the business segments behind these two broad categories (cyclical and non-cyclical). Let’s also split out the equity portion of how these companies finance themselves into the various sleeves. We have used the table in Exhibit 2 previously to help illustrate where our investments lie in the context of the whole North American Energy Industry.

Exhibit 2: Segment and Finance Detail of North American Energy Industry

Source: Factset. EIP calculations based upon Factset data as of 3/31/17.

3 YieldCos are publicly traded entities that own, operate and acquire contracted renewable and conventional electric generation that typically sell the electricity produced under long-term fixed price contracts with electric utilities or other end-users. YieldCos also invest in thermal and other infrastructure assets such as pipelines, storage and terminaling facilities. Like MLPs, YieldCos generally seek to position themselves as vehicles for investors seeking stable and growing dividend income from a diversified portfolio of relatively low-risk, high-quality assets.

The business segments colored in beige are the non-cyclical segments in which our portfolio is concentrated: poles & wires and pipes & tanks. But let’s talk about the different sleeves of equity:

- The “Utility” category includes companies like Southern Company, NextEra and TransCanada Corporation with an average dividend payout ratio of about 65%. There tends to be consistency across companies in this asset class in terms of the payout (Source: Factset, 3/31/17)

- The “MLP” category includes companies such as Enterprise Products Partners and Plains All The average payout ratio for MLPs is about 130% of earnings and about 100% of free cash flow with significant variance between the companies. (Source: Factset, 3/31/17)

- The “YieldCo” category includes any company taxed as a “C” corporation but with an implicit or explicit promise to pay out most or all available free cash This category includes NextEra Partners, which holds some of the long-contracted solar and wind assets of its parent, NextEra Energy, Inc. It also includes a number of MLP parent corporations like Oneok and some Canadian midstream companies that were, at one time, formed as income trusts but retained that high payout ratio after that structure was eliminated by the Canadian tax reform legislation in 2007. (Source: Factset)

- The “All Other” category includes companies like ExxonMobil, Haliburton, Conoco Phillips, Anadarko and Chesapeake This is normal common equity that on average, over time, pays out a comparatively much lower portion of earnings as dividends.

The Creation of Sponsored Entities

From this perspective, one can observe that the businesses with more stable cash flows have migrated to the higher payout sleeves of equity while at the same time being able to sustain more debt. This makes sense to us, as stable cash flows can bear more debt and the higher returns (historically, high single digit to low double digit) that accompany these stable businesses, call for a higher dividend payout ratio as these industries only grow 1- 3% per year. A business earning a 10% return on its assets that reinvests 70% of its earnings (the retention rate on average for the S&P 500) would grow its asset base 7% per year. That makes no sense in an industry that grows 1-3% per year.

But the higher payout ratio of the MLP and YieldCo sleeves reflects an implicit promise being made to investors that management is making, in hopes of getting a higher valuation, and therefore, a lower cost of financing.4 These are two sides of the same coin. Think about the debt markets where a company is trying to lower its interest cost (bond yield) by backstopping that debt with promises of a claim on assets (secured debt) and agreements to limit other borrowings (known as debt covenants). This says to the bondholder, “I will pay you back the money I owe you before I borrow any more.” Companies issuing public equity are likewise trying to lower the earnings yield on the equity they issue by making similar promises. A higher dividend payout ratio says to the investor, “I will pay you first before I commit new capital to grow our business.”

The trial and error and fluidity of the capital markets has encouraged the industry to migrate its more stable infrastructure asset-driven cash flows into the higher payout sleeves of capital. This behavior can also be observed on a company-level basis. Take Shell, for instance: it has spun out an MLP that holds a small portion of its pipeline assets with steady cash flows. This MLP, Shell Midstream Partners (ticker: SHLX), holds about $6 billion of assets. SHLX trades at about 20 times this year’s estimated earnings, while the parent company (RDSA NA) trades at about 15 times. Shell has another $30 billion or so of pipeline and related assets that it will drop down into SHLX over the next five years or so provided this valuation advantage is sustained.

4 We use the phrase “cost of financing” rather than “cost of capital” because we think it is more precise. Capital is a term that can connote assets or liabilities. A company’s plant and equipment is capital. A company’s debt and equity is its financing.

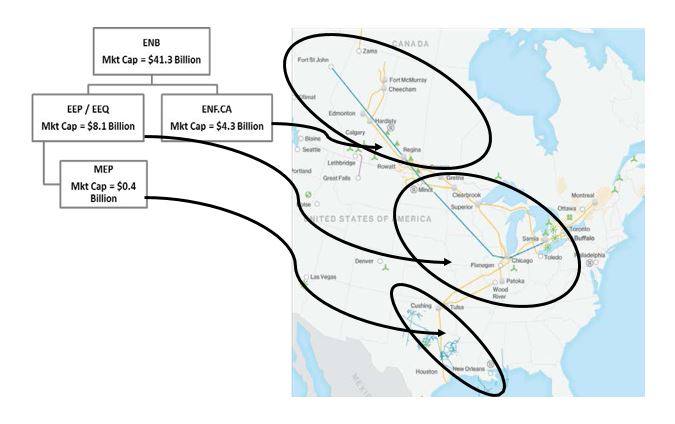

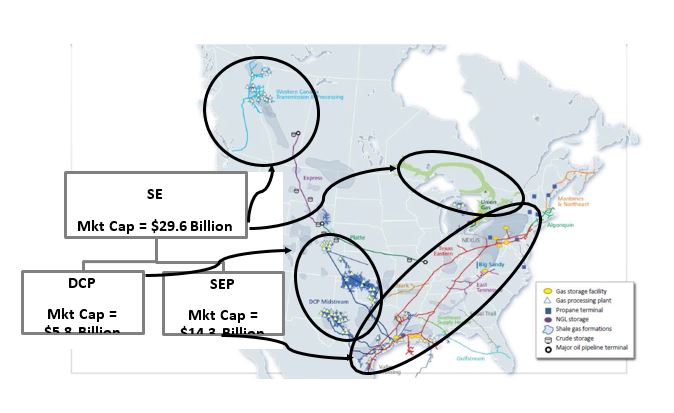

Another example is Enbridge Inc. and Spectra Energy Corp, which recently merged into one company retaining the Enbridge name. Exhibit 3 shows how their sponsored entities (or daughter organizations) fit into their asset footprint.

Exhibit 3 – Corporate Structure of Enbridge and Spectra

Enbridge Inc. Corporate Structure & Assets

Source: Enbridge Investor Presentation from 4Q 2016, Bloomberg. The above information is shown as an example of corporate structure and where the underlying assets are located. This is not a recommendation or an offer to purchase or sell a particular security, nor is it a statement with respect to EIP’s opinion on the companies shown.

Spectra Energy Corporate Structure & Assets

Source: 4Q Investor Supplement from Spectra Corp, Bloomberg. The above information is shown as an example of corporate structure and where the underlying assets are located. This is not a recommendation or an offer to purchase or sell a particular security, nor is it a statement with respect to EIP’s opinion on the companies shown.

Each of these companies had spun out two sponsored entities. Spectra had spun out two MLPs, while Enbridge had spun out one MLP in the US (which in turn spun out its own MLP) and an income trust (now a YieldCo) in Canada. The map shows the assets held in each of these sponsored entities. Enbridge has indicated that it plans to simplify its structure somewhat but not eliminate all the sponsored entities.

The MLP space is full of situations like this. In fact, more than half the MLPs in our portfolio are sleeves of capital of much larger corporations, while very few are true stand-alone companies. Exhibit 4 shows a sample of the more significant MLP spin outs of the last few years.

Exhibit 4 – Recent MLP Creations and Corporate Restructurings

Source: Corporate Reports and EIP Estimates. EIP believes these transactions are both material and representative of all the corporate transactions affecting MLPs over the last 10 years. The information above is shown as an example of the larger spin out and consolidating transactions in this space. This is not a recommendation or an offer to purchase or sell a particular security, nor is it a statement with respect to EIP’s opinion on the companies shown.

Creation and Destruction of MLPs as Sponsored Entities

So, whether we are looking at an industry level or at a company level, a high payout entity like an MLP or a YieldCo is usually created because it lowers the cost of equity financing. So, why then are we now witnessing the consolidation, or simplification, of corporate structures that result in the elimination of the MLP sleeve of capital? Exhibit 5 shows some of the recent simplifications.

Exhibit 5 – Recent MLP Eliminations and Corporate Simplifications

Source: Corporate Reports and EIP Estimates. EIP believes these transactions are both material and representative of all the corporate transactions affecting MLPs over the last 10 years. The information above is shown as an example of the larger spin out and consolidating transactions in this space. This is not a recommendation or an offer to purchase or sell a particular security, nor is it a statement with respect to EIP’s opinion on the companies shown.

The simple answer is because those MLPs are no longer reducing the overall company’s cost of financing. So, why or how does that come about? There are two ways this can come about.

- First is that the set of promises that initially led the MLP to trade at a higher valuation than the parent corporation (or for stand-alone MLPs, a higher valuation than a stand-alone corporate structure with a lower payout ratio) has been This would occur because the cash flows backstopping the dividend declined as they often do in cyclical businesses like oil and gas production, shipping or gas processing (the latter two of which are “midstream” activities). Once you break a promise and cut the dividend, the market tends not to forget, demanding a higher yield (lower valuation) to compensate for the risk. Over the last 2 ½ years, about 40% of the MLPs in the Alerian MLP Index have cut or eliminated their dividends.

- Second, and this is unique to MLPs, is that the MLP was very successful in growing its dividends for a long period of That’s right, both failure and success will ultimately lead to a higher cost of financing. The reason success can lead to a higher cost of financing has to do with incentives paid by the limited partners (LP) to the general partner (GP). These incentives increase with per share dividend growth at the LP level and are due on newly-issued shares, as well as older shares that have experienced the growth. The table in Exhibit 6 illustrates this arithmetic.

Exhibit 6 – How GP Incentive Distribution Rights Grow Over Time

Source: Corporate Reports and EIP Estimates. This is an example of how EIP believes a typical GP incentive works, it is not meant to be representative of any particular company.

In the typical MLP structure, the entity that initially brings the MLP public operates the assets and holds the general partner interest, and that generally gives it super-majority rights. The GP begins with a 2% economic interest but if the per share free cash flow and dividends (we are assuming a 100% payout of free cash flow) grow at the LP level, the GP gets to share in the increment. Typically, that sharing moves through tiers of 15%, 25%, and 50% so that when the LP per share distributions are about 75% higher than at the IPO, the GP is getting half of all incremental growth. Newly-issued shares have the same 50/50 split, even though those new shares have not yet grown their per share distributions by 75%.

This incentive originated in the early 1990s when MLP IPOs were difficult because of all the failed oil and gas production MLPs formed in the 1980s, soon after the spike in oil prices caused by the Iran/Iraq war. To make MLPs more attractive to investors, the GP sponsor had to subordinate its LP shares to the public’s shares. Since the GP often retained about half the shares, this subordination provided protection to the public shareholders of a roughly 50% decline in earnings. The incentive to grow the dividend was compensation to the GP for providing this insurance policy.

If an MLP is successful at growing its dividend over many years, the GP share of all free cash flow can get very large. In this example, after 15 years the GP is taking 36% of all the MLP’s free cash flow, about equal to the corporate tax rate. When Kinder Morgan consolidated all its entities into the parent corporation in 2014, the parent, Kinder Morgan, Inc. (KMI) was taking 46% of all the free cash flow from Kinder Morgan Partners (KMP). It took 22 years for the GP share to rise from 2% to 46% and over that time, the dividends grew at a compounded rate of 11.7% annually.

The impact that this kind of success has on the cost of financing can be seen in the columns to the right in Exhibit6. Assuming the MLP trades at a 7% yield, the total cost of equity financing rises over time as the GP’s share rises. In the first year, when the GP’s share is only 2%, the cost of equity financing is a little over the 7% going to the LP unit holders. By year 15, the MLP in our example pays out a 7% yield to the LP unitholders ($5.73 in our example) and 4% to the GP ($3.27 in our example) for a total cost of equity financing of 11%. This expensive equity makes finding accretive growth more and more difficult in an industry full of regulated assets that offer 10-12% returns on equity.

Now that some of the MLPs that came public in the 1990s and the early 2000s have been successful for a long period of time, the inevitable arithmetic in Exhibit 6 is coming home to roost. So, the more successful the MLP is in growing its dividends, the closer it gets to ultimately re-combining itself with the parent corporation or conducting some other transaction that eliminates the pernicious effect those IDRs ultimately have on the cost of equity financing.

We have had meetings during which potential investors were concerned that EIP does not have enough exposure to GP interests, expecting the growth to continue forever because they may not be familiar with this arithmetic. Since EIP is familiar with this arithmetic, we have very little exposure to these disappearing payments from the LP to the GP.

Exhibit 7 shows the 30 largest MLPs in the Alerian MLP Index. Those colored in blue have done a simplification transaction of some sort that eliminated the IDRs or preemptively reduced the top sharing tier for the GP, to avoid the need for a simplification transaction. We have colored as blue the Energy Transfer family of companies as the company’s management has already indicated that something will be done eventually to unburden the company of its IDR obligations. As you can see, the MLPs colored in blue represent a significant portion of the market cap of the MLP index (68%).

Exhibit 7 – MLPs That Have Eliminated IDR Payments

Source: Corporate Reports, Factset, Bloomberg and EIP Estimates for the largest 30 MLPs in the Alerian MLP Index as of March 31, 2017. This is not a recommendation or an offer to purchase or sell a particular security, nor is it a statement with respect to EIP’s opinion on the companies shown.

Wrapping Up

This unusual incentive structure is unique to MLPs and is a result of historical circumstances surrounding the widespread failure of the oil and gas production MLPs in the 1980s. While most discussions in the investment world center around industry and macro-economic factors combined with how individual companies cope with those dynamics, there is very little discussion about the financing side of the equation. For most equities, that makes sense, as the type of equity and debt they use is common among them. But in the energy infrastructure space, the financing side of the equation has been critical in understanding the investment merits and investment risks. Due to the highly cyclical nature of some parts of the energy industry and the highly stable nature of other parts of the industry, small changes in the mix of assets held by a particular company can have large consequences. Such consequences then have a knock-on effect to the financing side, given the stark difference in the valuation the market is willing to assign non-cyclical cash flows versus cyclical cash flows. Add to that the dynamic of how these incentives paid to the GP from the LP change over time, and you can see why most investors lose their bearings when they try to invest in this space–naively thinking that MLPs are simply a proxy for “non-cyclical energy infrastructure.”

If only it were that easy!

We are glad it’s not that easy.

Best regards,

James J Murchie

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Performance information provided for the Energy MLP Income Fund (EMIF or the “Fund”) assumes the reinvestment of interest, dividends and other earnings and is net of fees. There is no assurance that the Fund’s investment objective will be achieved.

The EMIF portfolio information regarding dividends and portfolio company prices is provided as an example of EIP’s investment philosophy and strategy and not an offer or sale of any security. Information in this letter regarding specific MLP instruments and other companies, including any information pertaining to the performance of such instruments and other companies, is provided solely as a tool for general industry analysis. Under no circumstances should it be assumed that the Fund or any other account managed by Energy Income Partners, LLC derived any benefit from the performance of any MLP or company referenced herein. Information provided is believed to be accurate as of the date on the materials. EIP reserves the right to update, modify or change information without notice. The information is based on data obtained from third party publicly available sources that EIP believes to be reliable but EIP has not independently verified and cannot warrant the accuracy of such information. This Document is not an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security. This Document is strictly confidential and may not be reproduced or redistributed in whole or in part nor may its contents be disclosed to any other person under any circumstances. This Document is not intended to constitute legal, tax, or accounting advice or investment recommendations of any particular security or industry. Investors are encouraged to conduct their own analysis before investing.

CIRCULAR 230 NOTICE. THE FOLLOWING NOTICE IS BASED ON U.S.TREASURY REGULATIONS GOVERNING PRACTICE BEFORE THE U.S. INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE: (1) ANY U.S. FEDERAL TAX ADVICE CONTAINED HEREIN, INCLUDING ANY OPINION OF COUNSEL REFERRED TO HEREIN, IS NOT INTENDED OR WRITTEN TO BE USED, AND CANNOT BE USED, BY ANY TAXPAYER FOR THE PURPOSE OF AVOIDING U.S. FEDERAL TAX PENALTIES THAT MAY BE IMPOSED ON THE TAXPAYER; (2) ANY SUCH ADVICE IS WRITTEN TO SUPPORT THE PROMOTION OR MARKETING OF THE TRANSACTIONS DESCRIBED HEREIN (OR IN ANY SUCH OPINION OF COUNSEL); AND (3) EACH TAXPAYER SHOULD SEEK ADVICE BASED ON THE TAXPAYER’S PARTICULAR CIRCUMSTANCES FROM AN INDEPENDENT TAX ADVISOR.

These materials do not constitute an offer of securities. Such an offer will only be made by means of the Confidential Memorandum to be furnished to prospective investors at a later date. This document is confidential and is intended solely for the information of the person to whom it has been delivered. It is not to be reproduced or transmitted, in whole or in part, to third parties, without the prior written consent of the Fund. Notwithstanding anything to the contrary herein or in the Confidential Memorandum, the recipient (and each employee, representative or other agent of such recipient) may disclose to any and all persons, without limitation of any kind, the tax treatment and tax structure of (i) the Fund and (ii) any transactions described herein, and all materials of any kind (including opinions or other tax analyses) that are provided to the recipient relating to such tax treatment and tax structure.

A description of the Alerian MLP Total Return Index may be found at http://www.alerian.com/indices/amz-index/. The index performance is provided for information purposes only. The Wells Fargo Midstream MLP Total Return Index consists of 53 energy MLPs and represents the Midstream sub-sector of the Wells Fargo MLP Composite Index. The index is calculated by S&P using a float-adjusted market capitalization methodology. S&P 500 Index: A capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks. This Index is designed to measure performance of the broad domestic economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries. The indices have not been selected to represent an appropriate benchmark with which to compare an investor’s performance, but rather are disclosed to allow for comparison of the investor’s performance to that of certain well-known and widely recognized indices. An index is unmanaged, does not incur fees or expenses and an investment cannot be made directly in an Index.